The Irish Sea-Racing Pigeon Strain

The Irish Sea-Racing Pigeon Strain

Irish Sea-Racing Pigeons

Although not a specific strain, family or colony of pigeons, the Irish Sea Racing Pigeons are a modern (in real time terms) group of racing pigeons which have been honed, conditioned and cultivated around their ability to fly long distances over large expanses of water for considerable periods of time, through some of the worst weather known on the western coastline of the Atlantic Ocean over the past 100 years or so.

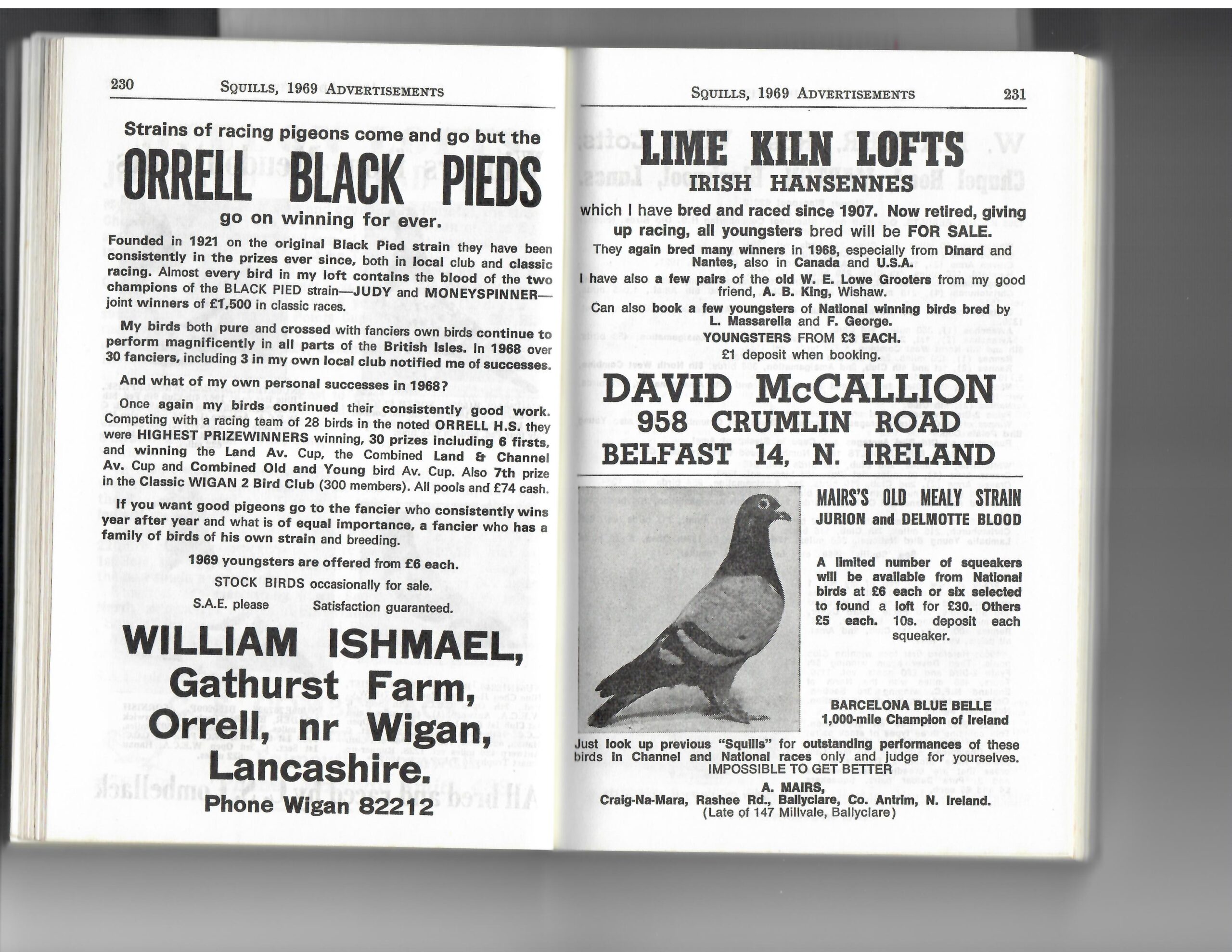

Racing pigeons, as a sport, has been in Ireland for well over 100 years, since the late 1880’s. Traditionally, our business interests forged strong links with Belgium through the textile industry at the turn of the 20th Century. There is clear evidence that the pigeons of Hanseene, Commines, Wegge, Jurion, Delmotte, Puttman and others were making their way from Belgium to Ireland – and being tested on our terrain and environments from early on.

As the sport became popular, and transport became easier, we began to see imports of what are better known strains and families of birds such as those from Jules Janssen, Dr. Bricoux, Van Der Espt, Maurice Delbar, Georges Busschaert amongst many others.

Irish fanciers began to visit the lofts of these Belgian champions, to forge relationships, and ensure that the best of these families were coming to the Irish lofts due to the very extreme conditions that our racing pigeons had to face – namely the Celtic Sea and Irish Sea. Not many pigeons in the world are expected to head out across open ocean for distances between 200 and 500km of open water, and be expected to be seen again!

Thus, over a period of over 100 years now, we have been refining and selecting the pigeons that can undertake this arduous task of flying across large expanses of water, in cold and often wet conditions, with fog and predators to contend with, all for the love of their home loft.

Some extraordinary results have been achieved in this period. “Barcelona Bluebell” in 1965 raced from the Spanish racepoint of Barcelona (1600 KM +), she had already completed 4 flights from France at 900km each. “Ulster Queen” raced from San Sebastian into Northern Ireland at similar distances – proving that these extraordinary feats over water can be completed.

In modern Irish Pigeon Racing the distances are not quite so far, but the blood of the ancestral pigeons is maintained, and the selection process is still very robust. It needs to be because as young pigeons they are expected to race to 500 KM across the Irish Sea from Britain, and there are even examples of these young birds completing the crossing from France (900KM) as young as 7 months old. This type of racing is not for every family of pigeons, and it is well documented that many of the so-called “famous” racing pigeon families simply cannot perform the tasks asked of them over the sea from Ireland. Many of the famous Dutch and Belgian families will only do so after they have been tested and selected over a number of years, and the input of the “older” blood is added to the breeding, will they perform.

Modern additions to the long distance blood that works, following testing and selection, include the Janssen, Delbar, Busschaert, Kenyon, Bricoux, Jan Theelan, Barker, Walkinshaw, Van Der Wegen, Van Wanroy, and Stichelbaut lines from the fines lofts in Europe – as stated earlier, none worked immediately, more like they endured over a protracted period of testing having been blended into other families of Irish Long Distance Pigeons – full of bravery, tenacity, orientation and character.

We continue to “trial” all of the latest “fad” breeds, such as the Jellema pigeons and other families that are making their mark in Europe over land on the long races, but our history of hard testing and selection on our routes across the sea makes it difficult for these “new” families of birds to adapt – no matter what they have achieved elsewhere.

Pathfinders

For the channel and French racing in Ireland, the fanciers will have been busy breeding pigeons from the narrow gene pool of successful pigeons which have negotiated these tough racing conditions for the past 100 years or so.

Racing in Ireland, for any pigeon, begins in the year of its birth, when the racing program will concern mostly inland racing of between 100 – 300km. This involves the birds having to navigate the mountainous terrain and damp weather conditions which prevail in our country. Often the birdage for these races will exceed 30,000 birds. The last races of the year involve flights across the Irish Sea to Britain, to either Talbenny in Wales or to Penzance in Cornwall, both of which involve maritime flights of at least 250km over water, and perhaps 250km on the longer race points. This is how our pigeons are selected – no room here for the weak or non-brave birds.

In the second year of their racing lives, the birds which are bred for the medium and long distance races, will be racing in the shorter races as a form of training and conditioning, with their nest condition being prepared to provide the best motivation for the longer sea races which will be ahead of them. A favoured nest condition is to send the birds on chipping eggs or sitting a large young bird in the nest. Some fanciers will be looking to allow their birds to mature to being 2 years old before sending them to the marathon distances, so they will send them to the shorter sea races in their yearling stage, hoping to give them some experience before sending them to the major races the following year.

Other fanciers skip this middle stage and send their yearlings, some only 7 months old, to the longest races, and have even had some huge successes with this method. These races are truly a test of a pigeons’ character, with the distance over the sea, the weather, predators, wind direction and willingness to race all coming together to either help, or work against, the chances of having a successful flight from these most difficult racepoints.

Flying home from these sea races, the pigeons depart the coastline in small bunches of perhaps 10 or so birds, as they fly across the sea, it is noticeable that if the weather is poor, that the birds will “hop” across the top of the waves, where they can benefit from some uplift from the air movement closest to the wave tops. As the flight gets longer, these small groups become smaller and as they approach either Great Britain or the landmass of Ireland, the bird groups will reduce further as some birds will tire and will land for some rest. The best pigeons will continue, almost always alone, to their home lofts which will often be hundreds of kilometres away still. This is a very brave thing for a pigeon to do, as they are a flock bird and prefer to fly in the company of other birds.

Winning velocities obviously depend on the wind, and any race that is won above 1000m per minute is regarded as an easy race. Many of the races are “smash races” (less than 10% of the convoy home over 3 days), and the race has been won with a velocity below 700 mpm on many occasions. There are instances of less than 10 birds returning from a convoy of 2000+ birds, and many birds have returned on the winning race day as the single bird to reach home within the day of liberation.

Racing into Ireland, with our long distance marine races is not for the weak fanciers, to win they must send their best, and expect them! Thousands of “good” pigeons have never been seen again with these races, and yet others have flown in the prizes as many as 3, 4 or 5 times. These families are the ones that get retained into the gene pool, and have been contributing to this pool for many, many years. Nowhere else in the world are racing conditions so tough, that fresh” blood cannot be expected to compete with the specialist families that are experienced at doing these races.

A History of Selection

It is often noted that many things come about through necessity. In older times, when poverty pervaded with the working class, there was simply no room to carry “passengers”, be they Dogs, Horses or Pigeons. If the animal couldn’t perform to the standard required, it was disposed of or moved along to someone else. The food required to keep working animals was too expensive to be giving to underperforming individuals – and this worked a form of selection for many generations.

Our ability, as Irish people, to manage, blend and improve breeds of animals is known throughout the world through mainly the horse industry. Our horses are sought after and underpin most of the strong genetic lines anywhere -whether they be racers, jumpers, hunters or simply for show. Our environment has shaped this development, at times a shortage of money as mentioned above, our climactic conditions, our terrain, our genetics as nomadic herdsmen and, once developed, our keen eye for detail.

It is known that many strains and families of pigeons which came to our shores either directly from Belgium and Holland, or indirectly through Great Britain, have returned to their home countries, having been put through our testing and selection process, which, as is now commonly known, leaves little to the imagination. The genes and bloodlines of over 100 years of selection and breeding do not tell any lies, and although not all pigeons bred from this background turn out to be superstars, it is acknowledged that these birds are the perfect base to start from.

Pigeons which come from Belgium or Holland do not arrive here at our shores capable or willing to fly over large expanses of water. Following the training, testing and racing, not to mention the selective breeding process, within a period of 10 or more years, those families that succeed can be seen to be performing at these distance races.

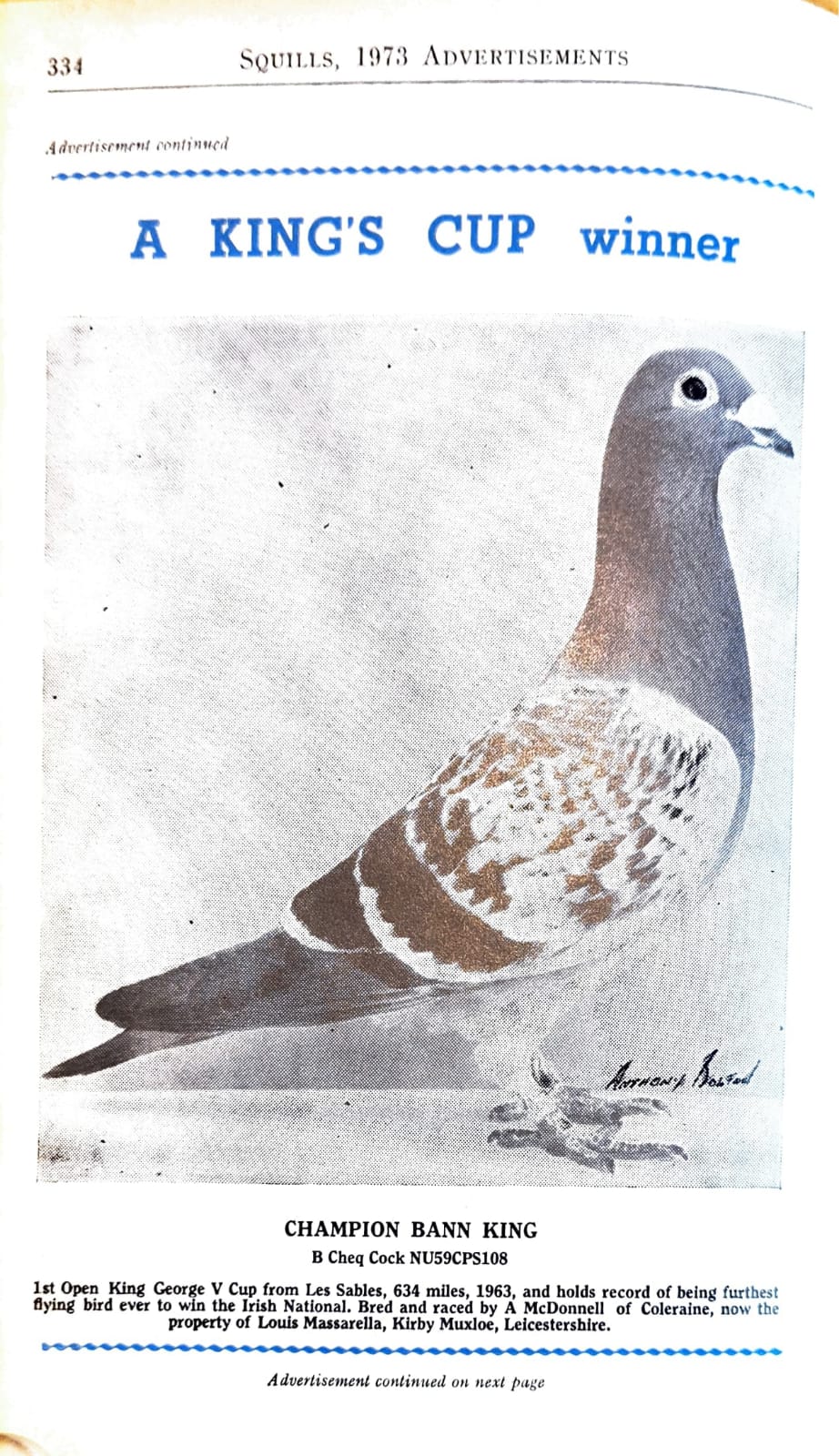

It is an accolade for a racing pigeon to perform in the prizes from our most important race “The Kings Cup” which is flown from France every year. “Open” prizes are normally awarded to the first 200 places, if that many pigeons return in race time (normally 3 days). The average return from this race is probably around 10% of entrants – entry is normally between 2,500 and 3,000 birds.

Since 1970, for pigeons that perform in the prizes 3 times, they receive what is known as a “Hall Of Fame Diploma” award, this is a great honour to the bird and to the owner and breeder of the bird. It is a difficult feat to achieve for both fancier and bird, and has been achieved less than 200 times in 50 years.

A further award of a “Gold Medal” is awarded to pigeons which manage to go on to race a further time (4 times) in the prizes – this number of awards is less than 15 in 50 years. Additionally, a special award is also offered for pigeons which race the Youngbird National Race, The Yearling National Race and the Kings Cup – all in the prize positions, known as “The Triple Crown” award. This has only been completed 9 times in 10 years. These birds are very special athletes, and it just shows to prove how difficult and testing our race routes are.

From the same “King’s Cup” race – The “Harkness Rosebowl” is awarded to the loft with the 2 fastest returning birds from the race, and often these birds are paired together for future racing. Additionally, and finally, a single bird challenge competition is held whereby the fanciers must nominate a single bird of their flock who they reckon will return fastest from the race. It is a great occasion in our racing season as it is the fruits of many months and years of preparation for many of the participants.

We have quite a few families from this unique strain of pigeons in our breeding lofts – initially as a fail-safe against the genetic lines being lost and latterly to provide a base for the next generations of maritime racing birds – looking to create their own legacy.

Ask us about our Dolly, Brooks or Cordner families. Highly proven on the difficult route between Ireland and the UK and and France over the past number of years, birds that have bred their like on a regular basis.